On the night of april 21st 1943 a Stirling bomber was shot down over Denmark. Only one of the crew members, Donald Smith, survived the crash. After having walked across Sjaelland he came in contact with the Danish resistance and was helped to Sweden. But the story didn’t end until 1999, when Smith’s ashes, at his request, were interred alongside his crewmates in Denmark.

by Dave Smith

This article has been written by Dave Smith, son of Donald Smith – the only survivor of a Stirling bomber that was shot down over Denmark in 1943. Donald Smith died in 1998, and at his request his ashes were interred alongside the graves of his crewmates, at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Svino in Denmark

I also knew that they had a steady diet of mutton and Brussels sprouts that resulted in a lifetime dislike for those foods. When driving he never passed a hitchhiking serviceman without stopping to offer a ride. We had many visits from his air force friends but he never talked about his experiences during the war.

This led me to the mistaken impression that he had spent the entire war without any excitement. As it turned out, nothing could have been further from the truth.

In the spring of 1968, my mother was listening to the radio and there was an announcement that a Mr. Jorgen Helme from Denmark was trying to locate a Sgt. Donald V. Smith from Toronto. He was researching Allied air operations over Denmark in World War II and had discovered from his searches of Department of National Defence records that Don had been the sole survivor of a plane crash, had managed to find his way across the island of Sjaelland, make contact with the Danish Resistance and to escape by kayak to neutral Sweden, thereby becoming the first Allied airman to escape from occupied Denmark.

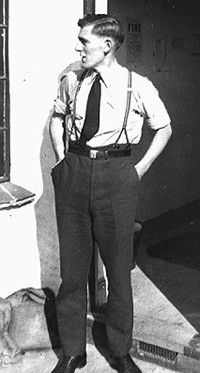

Flight Engineer in the Royal Canadian Air Force (R.C.A.F)

At the urging of my mother and brothers, my father dug out a little black booklet and read us an astounding account of bailing out of a flaming bomber, landing in a freshly plowed field, making his way across Sjaelland, and by relying on help from Danish civilians, paddling across cold, rough water on the Sound to Sweden, where he was thrown into jail for a few days for illegal entry before being granted refugee status.

The Mission

It all had begun on the evening of April 20, 1943. A major bombing operation was launched from bases in England against numerous German targets. Among the planes taking part in the raid was a Stirling bomber, M for “Mother”, of the 7th Squadron Pathfinders. The plane had a mixed crew of men from the British Commonwealth:

- Flt. Lt. Charles Woodbine Parish Pilot R.A.F

- P/O E. R. (Bob) Vance Navigator R.C.A.F

- Flt. Sgt. J.S. (Jimmy) Marshall Bomb Aimer R.C.A.F.

- Flt. Sgt. Louis Krulicki Wireless Operator R.C.A.F.

- Sgt. Charles Farley Mid Upper Gunner R.A.F

- Sgt. Jack Lees Rear Gunner R.A.F

- Sgt. Donald V. Smith Flight Engineer R.C.A.F

Their destination that night was Stettin, and their mission was to locate the target area and mark it with incendiaries as a guide for the rest of their planes. They had an extra crew member that night, S/L Blake, a Canadian pilot who was new to the squadron and who was to accompany them on an orientation flight.

Their aircraft was damaged by flak on approach to the target and, unable to mark it reliably, they aborted and left the job to a backup plane. Heading back to England, they flew over the Baltic and the relative safety of the water. As they approached Korsor, they had to veer across land to avoid a flak ship in the Belt, but soon found themselves under attack by an ME 110 night fighter. After a burst of cannon fire set their plane afire, the order was given to bail out.

Don Smith was the only one who managed to escape from the plane before it crashed into a farmer’s field near Kongsmerk. Landing a few fields away from the crash site, he buried his parachute and set off at a walk run to put as much distance as possible between him and the plane, knowing that the Germans would soon arrive to investigate. An extra crewmember on board that night might have misled the Germans into thinking that the entire crew had perished and that there were no survivors.

On the run

Over the next few days, Don kept up a steady pace in an easterly direction, keeping to fields and rural areas to avoid German soldiers. He had been injured in the escape. His hands were badly cut and his nose had been broken. He was tired and hungry, and his feet were badly blistered from the chafing of his flight boots.

Don desperately needed help, and he approached Danish farmhouses to ask for food, water and directions. In most cases, the people did not speak English, but they were able to communicate with sign language. He was never turned down by any of the people he approached, and more importantly, he was never turned in, even though helping an Allied airmen would have brought swift and severe reprisals to any Danes caught doing so.

Don made it across to Copenhagen and then up to Helsingoer (Elsinore), just a few miles across the Sound from freedom in Sweden. The only problem now was to find a way across. He had hoped to find a small boat, but they had all been taken away or locked up by the Germans, or they were under guard by armed soldiers.

Almost ready to give up, but having had so much luck in getting help from loyal Danes, he once again approached a home where he saw a Danish flag flying. He was lucky enough to have found someone who had friends in the Danish Resistance. After carefully checking and verifying his identity, the Resistance agreed to help him get across to Sweden.

While some of the Resistance workers were busy finding and repairing an old kayak, Don and a young police cadet, who was also escaping from the Germans, were taken on a sightseeing tour of Copenhagen by a young lady from the Movement.

On the last day in Denmark, they spent the afternoon at a cafe near Skodsburg. Later that night, some young girls with the Resistance distracted the shore patrol while Don and his partner were pushed off into the cold waters of the Sound.

Escape and return to England

Unlike previous escape attempts from Sjaelland, they arrived safely in Sweden a few hours later. They reported to the British Legation, later turning themselves in to the Swedish police and were charged and jailed for illegal entry. A few days later they were released and sent on to Stockholm, where they eventually caught a commercial flight to Scotland.

Don Smith was the first allied airman to escape from occupied Denmark. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal, which was presented to him by King George VI. Many more were to follow his lead, as the Danish Resistance became increasingly effective in its fight against the Nazis.

Don was sent back to Canada on a one month leave. He returned to England but did not fly on any more operations. He went back to Canada in 1944 and was based at Boundary Bay in British Columbia, where he was involved in pilot training until the end of the war. He went on to a career in the aircraft industry, working for A.V. Roe, was involved in the AVRO Arrow project, and later worked for Union Carbide Canada in Welland Ontario. In his spare time he was involved with the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, serving as commanding officer of the 23rd Squadron (St. Catharines) and later with the Air Cadet League of Canada where he helped to co-ordinate the glider flying program and international air cadet exchange.

Back to Denmark

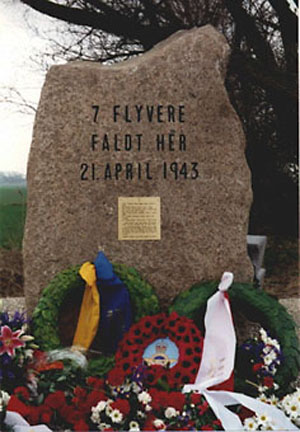

In 1968, after being contacted by Jorgen Helme, Don travelled to Denmark where he and Jorgen retraced his escape route. He had the opportunity to meet many of the people who had helped him in 1943. He went back to Denmark several times, the last visit in April 1993, for the unveiling of a monument in Kongsmark commemorating the 7th Squadron and the crew of his plane.

Don Smith died in 1998. He had requested that his ashes be interred alongside the graves of his crewmates at Svino, a wish that we were happy to honour, but had no idea how to go about. The day after he died, we received a letter from Mr. Ron Wellings of Glostrup, an ex-patriate “Brit” living in Denmark and member of the local historical society. We contacted Ron and he was most helpful in putting us in touch with the right people.

“The Commonwealth War Graves Commision” indvilligede i at nedlægge asken ved gravstedet ved Svinø, men da det kun var for dem som døde i aktiv tjeneste under krigen var der betingelser; ingen ceremoni, ingen mindehøjtidelighed og ingen offentlig omtale af nedlæggelsen. Ron havde også kontaktet den britiske ambassade og “7th Squadron R.A.F. Association”. De havde udarbejdet et kompromis og forberedt en rejseplan som blev sendt til os nogle få dage før vor afrejse.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission agreed to inter the ashes in their site at Svino, but since it was reserved for those who died in active service during the war, there were conditions; no ceremony, no commemoration and no publicity. Ron had also contacted the British Embassy and the 7th Squadron RAF Association. Between them, they worked out a compromise and organised an itinerary that was sent to us just a few days before our departure.

In May 1999, two of my brothers, their wives and I set off to Denmark. I flew ahead with my father’s ashes and was to meet the rest of the family the next day. I was met at the airport in Copenhagen by Jorgen Helme and a friend who took me on a sightseeing tour of Copenhagen. We travelled up the coast to Skodsborg to see the beach from which my father and his escape partner set off to Sweden, and Jorgen pointed out the beach in Sweden where they landed. Then we travelled across the island to Menstrop where I was to meet my brothers.

The next day the five of us travelled up to Kongsmark for a wreath-laying ceremony at the monument that marks the site of the plane crash. We met Mrs. Elizabeth Horsworth, sister of the pilot, and her family, some representatives of the 7th Squadron association and a number of the townspeople who had been instrumental in the erection of the monument.

A walk through the field turned up bits and pieces of the plane. The man who farms the land explained that new debris turns up every year when he plows the field. The ceremony was followed by a wonderful luncheon at the town meeting hall.

The next day we drove to Svino for the Interment services. It was a gorgeous spring day and we were delighted to find the war graves site had been so beautifully maintained by the Church Council. We were very pleased with the arrangements that had been made in order to allow the service and commemoration for our father and later that evening attended the National Liberation Day ceremonies.

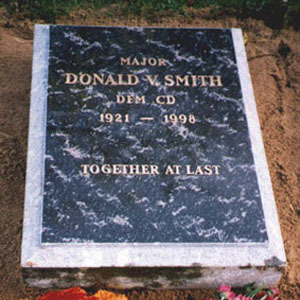

The gravesite of Don Smith is located at the boundary of the war graves site, just a few meters from the graves of his crewmates. His marker reads:

MAJOR DONALD V. SMITH

D. F. M. C. D., 1921-1998

TOGETHER AT LAST